Madeleine Carroll Biography

1906 -1925

It would be hard for the present day generation to appreciate just how big a Hollywood star Madeleine Carroll was in her day.

Madeleine Carroll was born Edith Madeleine Carroll in No. 32, Herbert St, West Bromwich, Staffordshire, England on February 26, 1906, the elder of two children of my uncle, an Irish professor of languages and his French wife.

In 1907, the numbering of the houses was changed so the house is now No. 44, Herbert St, which I visited for the first time in September 2005.

Her sister Marguerite (Guigette) was born 18 months later, in August 1907.

In 1912 the family moved to No. 7 Jesson Street, where Madeleine spent most of her childhood – a far cry from the glamorous world of Hollywood that she was later to encounter.

Her own life was focused very much around the family home, influenced very much by her mother, Helene, who taught her French, as well as many of the social graces which would be of huge significance in furthering her movie career later on.

Her early years were uneventful with many days spent dreaming

about a future where she could provide her mother in particular with the things she hadn’t got then.

She had many happy memories of spending many holidays in Co Limerick, Ireland, where her father was born in 1875.

“Family group taken on visit to Kilduff, Co Limerick. Madeleine is seated on the ground at bottom left, in front of her mother, whilst her sister Gigette is seated on the bottom right of the photo”

With her father’s tutorship, she matriculated from Birmingham University at the early age of 15, and by midsummer 1926, she was armed with her B.A degree, ready to teach or to go to the Sorbonne in Paris, where he father had studied before her.

1926 -1945

Madeleine proved a very bright student, and had been enrolled at the University of Birmingham with the intention of fulfilling her father’s choice of her profession as a teacher of French. “Everything indicated that I would spend the rest of my days teaching, ” she said years later. “I was shy, nervous … all through college. My father had set his heart on my getting an M.A. and all would have gone well if I had not joined a drama society in my senior year.

In March 1926, and then a student in French, I got a leading part in the annual play called “Selma”, and somehow I did it as if I had been acting all my life. I understood then how people get ‘a call’.”

Sir Barry Jackson, director of The Birmingham Repertory Theatre, saw her in “Selma” and offered her a contract which she declined on the insistence of her father, who vehemently disapproved of her theatrical ambitions. Receiving her B.A. in French with honours, she went to Paris for graduate study but returned almost immediately, determined to pursue a career in the theatre.

Her father ordered her out of the house (they were reconciled only after her first film) and to support herself she acquired a job as French instructor at a girls’ school in Hove (near Brighton). Three months, in between unsuccessful acting job hunting, was all she could tolerate there, so she switched to tutoring privately in Birmingham.

1927

After saving sufficient funds to travel to London, she continued pavement pounding there until early in 1927 when she was given a small part in the tour of a play by Cyril Campion called “The Lash”. She joined the production at the New Brighton in February 1927 and after its short run was out of work again until Sir Seymour Hicks signed her to a five year contract with his noted touring company.

Despite the unexpected brevity of the association, it enabled her to acquire some of the rudiments of acting technique, chiefly through the coaching of Hicks.

1928

There are several versions, with minor variations, of her entrance into movies. The most persistent indicates that she was released from her contract with Hicks to accept a part in a London play during the rehearsals of which she was screen tested and eventually selected for the feminine lead in a picture called “The Guns of Loos” (1928), which had it’s debut in Brighton.

Apparently she had earlier allowed a press agent to submit her name for the part in what has been described as “a contest with 150 applicants”.

“My role was a nice English girl with a cultivated background,” she has said. “Emotionally it was a part I could cope with, for it dealt with the kind of life I had known”. The picture was a success and overnight I had won a reputation. I went around feeling pretty important, not realizing that I wasn’t the least bit ready for such success and that only by chance had I been able to put the character across”.

“But I soon came to my senses. For the next part they gave me was in a melodrama called “What Money Can Buy” (1928). The girl I had to play was a pawn of circumstances, flung into prison wrongfully.

Needless to say, I was not equipped to play her and did a poor job. But the experience taught me many things – how little I knew, how much I wanted to be a good actress, and how I would have to begin to make up for lost time”. Her second film was “Pas si bête” (1928)

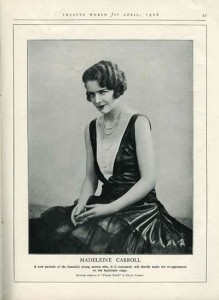

“Theatre World” for April 1928 had a photograph of the young Madeleine Carroll, with the following comment.”A new portrait of a beautiful young actress who, it is rumoured, will shortly make her re-appearance on the legitimate stage”

Her third film, “The First Born” with Miles Mander, is generally considered to be the one that established her.

1929

She made two more silents, “The Crooked Billet” and “L’Instinct” (a French film never released in Britain or the U.S.), before making her successful talkie debut in “The American Prisoner” (1929) opposite Carl Brisson.

Her popularity, as well as acting skills, increased steadily, both in films and on the London stage (where she appeared in ten productions between 1928 and 1931). These plays included revivals of Margaret Kennedy’s and Basil Dean’s “The Constant Nymph” (1928), John Van Druten’s “After All” (1931) and “French Leave” by Reginald Berkeley with Charles Laughton, which she repeated on film later the same year (1930)

Among the movies were E. A. Dupont ‘s elaborate Titanic-like adventure called “Atlantic” (1929), “Young Woodley” (John Van Druten’s play with Frank Lawton, (1930) and “Escape” (1931) with Gerald du Maurier and Edna Best. She also managed to fit in “School for Scandal” (1930) .

1931

During 1931, Madeleine appeared in “The W Plan” (1931), “The Written Law” (1931), “Madame Guillotine” (1931), Fascination (1931) and “The Kissing Cup Race” (1931). By the end of 1931 she was considered the top female star in British film industry and it was somewhat of a shock when she announced her retirement from the screen around this time, due to her recent marriage to Philip Astley of The Kings Guards, whom she divorced in 1939.

1933

Being “retired”, there was no Madeleine Carroll film in 1932 and just one stage appearance, but when Gaumont-British offered her a reputed £650 pounds a week contract the following year, she relented and made “Sleeping Car” (1933) opposite Ivor Novello and “I was a Spy” with Conrad Veidt and Herbert Marshall, both of which were popular.

“I was a Spy” (1933) was by far her biggest success up to that time and the first of her films to receive any decent bookings in the U.S., where it was distributed by Fox. The “British Film Weekly” selected her as Best Actress of the Year.

1934

Hollywood had been making her offers for several years and it was finally arranged that Fox borrow her from Gaumont-British on a one picture basis in exchange for Warner Baxter. Her U.S. debut was opposite Franchot Tone in “The World Moves On” (1934), an episodic saga of a Louisianian dynasty (1824-1924), which John Ford directed.

After completing “The World Moves On”, she returned to England with a press announcement that she would return to do “Call of the Wild” opposite Clark Gable. But Loretta Young eventually played the part.

1935

She then starred in an elaborate costumer with Clive Brook on loan to Topeliz films called variously, “Loves of the Dictator”, “The Dictator” and “The Love Affair of a Dictator”. Also in 1935 she made her last (to date) London stage appearance in “Duet for Floodlight”, directed by Cedric Hardwicke.

Madeleine Carroll’s place in film history is assured by her memorable performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s “The 39 Steps” (1935) which made both Hitchcock and herself international celebrities.

1936

She appeared for Hitchcock again in “Secret Agent” which, while hardly the critical and box office success of its predecessor, enhanced her reputation. It was released in the U.S. after she had arrived in Hollywood in January of 1936 with a Walter Wanger contract calling for four pictures.

In February she signed with Warner Brothers for a one-picture deal that was ultimately abortive and finally wound up on loan to Paramount in an ordinary programmer produced by Wagner called “The Case against Mrs Ames” (1936), billed in the ads as “the most beautiful woman in the world” and looking it.

Her part offered her little opportunity, but in her next “The General Died at Dawn” (1936) (also at Paramount), she gave perhaps her finest screen performance.

She then starred in two in succession at 20th Century Fox: “Lloyds of London” (1936) popular historical fiction that made Tyrone Power a star, followed by a guest appearance in “The Story of Papworth” (1936)

1937

Next came “On The Avenue” (1937), a musical with Dick Powell in which she was miscast (and not called upon to sing, incidentally).

Also in 1937 she appeared as Princess Flavia opposite Ronald Colman in the well remembered David O. Selznick-John Cromwell “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1937), a role that allowed her little to do save look beautiful and project nobility, which is how many remember her.

The success of “Zenda” left no doubt that the already popular actress had reached top stardom. Her salary was reported among the highest in the industry -(over $250,000) in 1938. She also starred in a minor light comedy at Columbia “It’s All Yours” (1937),

1938

In 1938, Madeleine made her second and final picture for Wanger. This was “Blockade”, a routine adventure but for the Spanish Civil War background that caused it to win far more attention than it would otherwise receive.

Nevertheless, the film was relatively daring by Hollywood’s incredibly bland standards and Madeleine went abroad the summer of 1938 to convince certain European censors to allow it to be shown. (In December 1937 she had been offered to star in the “first big Italian film ” “Carnival in Venice”, but declined. The film was apparently never made.

Also in mid-1938 the Wanger pact was dissolved and Madeleine signed a long term contract with Paramount, calling for two pictures a year. Here, due to her importance to a studio which would therefore “listen to me,” she hoped to “make important films, prooting world peace, ” she told Bosley Crowther early the following year.

1939

Instead she was initially cast in a light romantic comedy opposite Fred MacMurray called “Cafe Society” (1939) that proved popular enough for three subsequent teamings with MacMurray at the studio, together, the best of which is “Honeymoon in Bali” (1939). Then came “Virginia”, with Sterling Hayden, whom she would marry later. In 1939, she and Philip Astley were divorced.

1940

On loan out to United Artists in 1940 she was given top billing for what was really a supporting part in a popular soap opera with Brian Aherne called “My Son, My Son” (1940). Also that year she was reunited with Gary Cooper in “Northwest Mounted Police” (1940), from Cecil B. DeMille. She also made “Safari” (1940) with Douglas Fairbanks Jnr.

Her beautiful speaking voice made her a popular guest on radio programs and she starred in two series as well, the short-lived talk show called “The Circle” in 1938 and “Madeleine Carroll Reads”, in which she read from books.

On October 7th 1940, Madeleine’s sister Giguette, was killed during a German air raid on London. This had a tremendous effect on her life, and from then on, she began to focus her attention and life on the war effort, and dedicated herself to whatever she could do to help the victims of the war in Europe, particularly in France and on account of being half French.

1941

She teamed again with Fred McMurray in “One Night in Lisbon” (1941), and again with Sterling Hayden in “Bahama Passage” (1941), with whom she had already appeared in “Virginia”.

1942

She had became more and more preoccupied with the war effort, in between movies, and after 1940 her popularity began to wane a trifle, also due perhaps to the weakness of her films. Even so, as late as 1942, “My Favorite Blond” (1942), was one of her biggest hits, though primarily a vehicle for Bob Hope (for whom she proved a delightful foil).

On Valentine’s Day 1942, Madeleine Carroll and Sterling Hayden were secretly married in a house in the Palos Verdes Hills of California. However, World War Two parted them shortly thereafter and they were officially divorced soon after it was over.

Following the Bob Hope picture, Madeleine was able to get out of her contract so as to devote all of her time to the war effort. She joined the Red Cross. It is interesting to note that her name is down as Madeleine Hamilton, as this was the name she took along with Sterling Hayden, to avoid publicity.

1946 -1965

After the war Madeleine stayed in Europe where she conducted a radio program designed to aid French-American relations and helped in the rehabilitation of concentration camp victims (which brought her and her third husband, French Producer Henri Lavorel, together).

In late 1946 she went briefly to Switzerland to film a minor British soap opera “White Cradle Inn” aka “White Fury” (1946), and then returned to Paris where she and Henri Lavorel formed their own producing company and made several two-reel documentaries to “promote better understanding among the peoples of the world,” one called “Childrens’ Republic” was shown at the Cannes Film Festival.

“Childrens’ Republic” was filmed primarily to create an awareness of the devastation of children’s lives in Europe, caused by war. It was recorded in a small orphanage in the town of Sevres, just to the South West of Paris. It was shown primarily in Canada, where it was a strong source in raising funds for the manufacture of artificial limbs for the children whose lives had been shattered.

1947

In the fall of 1947, after an absence of 6 years, she and her husband came back to the U.S. to resume her career, so as to earn money to finance future films for their company. None were made, and they separated shortly afterwards.

1948

Madeleine made two films in 1948 , “An Innocent Affair” also k/a “Don’t Trust Your Husband” (1948) which was a reunion with Fred MacMurray and the type of romantic comedy they were making before the war. Her last movie was Otto Preminger’s version of “The Fan” also k/a “Lady Windermere’s Fan” (1949), from a story by Oscar Wilde.

On November 17th 1948 Madeleine made her first Broadway appearance as star of “Goodbye My Fancy” by Fay Kanin, at the Morosco Theatre in New York., and moved to the Fulton Theatre on February 7th 1949. During the play’s run she refused to allow her picture to adorn the cover of Life Magazine, while in September of 1950 she married the magazine’s publisher, Andrew Heiskell .

1949

Her success in “Goodbye My Fancy” provoked numerous stage and film offers all of which she declined in favor of a private life with Heiskell and, their daughter Anne Madeleine, born in 1951. She did, however, work briefly with UNESCO and made several (increasingly infrequent) appearances on television and radio until about 1964.

Following her direct experiences of the devastation in Europe during the war on children, Madeleine had proposed a resolution to the U. S. Committee of the UNICEF that there be constituted an International Children’s Day

On June 13th, 1949, Madeleine gave the keynote address to the first plenary session of the Rotary International Convention held in New York City. This speech embodied all her feelings about what was does to children, and her words confirm it. She told the audience why “I have constituted myself a one woman Children’s Crusade.” “

These TV appearances number about a literal handful, the most recent in 1964 (as narrator for Berlioz program music) and the best remembered in a 1950 television of “The Letter” on Robert Montgomery Presents.

During the late 1950s she starred as Dr. Gentry on a radio soap opera bearing that title. In 1964, amid much publicity, she accepted a starring role in a Broadway-bound comedy called “Beekman Place” also starring Arlene Francis and Ferdinand Gravet but during the tryout she resigned and was replaced by Leona Dana. The play opened and folded quickly to poor notices.

In January of 1965 she and Heiskell were divorced; they had been separated for nearly three years. Madeleine, who had become a U.S. citizen in 1943, had already moved to Paris, maintaining a residence in London as well.

“Movies?” she mused in an interview some years ago, “Just say I got out when the going was good.”

1966 -1987

Madeleine spent her years in retirement, living a life completely away from the world of Hollywood and fame.

The early years of retirement were spent in Paris. Her father had died in Farnborough (UK) in 1953, and was buried with Guigette in England. She first lived with her mother and her daughter in a beautiful apartment in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, and later, they moved to San Pedro in Southern Spain, where they lived in a large villa overlooking the Mediterranean, with apartments built specially for her mother and daughter.

Her mother died in January 1975, and was buried in Fuengirola. Anna Madeleine later went back to New York, where she unfortunately died in 1983, by which time Madeleine had moved to a smaller house on the beach, which she called “Casa Helena” after her mother, and where she lived quetly with her maid Anita who had been her constant companion for many years, and her two yorkshire terries, “Tricky” and “Dicky”, named appropriately after Richard Nixon !

She lead a quiet life, surrounded by her gardens and the sounds of the sea, and when the construction of a large apartment block was announced that would block part of her view, she quietly said “If you can’t beat them, join them”, and promptly bought a beautiful apartment with a vast terrace overlooking the sea, and moved in when the construction was all over.

She remained there until her death on October 2nd 1987.

Madeleine was buried alongside her mother in Fuengirola cemetery. Later, when due to planned building works the cemetery was to be demolished, a news reporter and writer called Lluis Molinas from the northern part of Spain heard about it.

Rather than have her remains and those of her mother transferred to a pauper’s common grave, he arranged for her remains and those of her mother to be transferred to a new burial spot in the Cementeri de Calonge, Cataluna, Spain.

She was given a formal reception by the local mayor accompanied by a band, and reinterred along with her mother with full honours in the town where she had made so many friends during her early years in Spain.

On February 26th 2010, she would have been 104 years of age – people are still celebrating the birthday on findagrave.com